At first glance Fotheringate Bay looks like just another classic Flinders Island granite beach setting.

Look more closely however and you can spot an array of limestone features around the precinct.

This is a rare example of coastal karst in Tasmania.

The H.M.S. Challenger and the forams

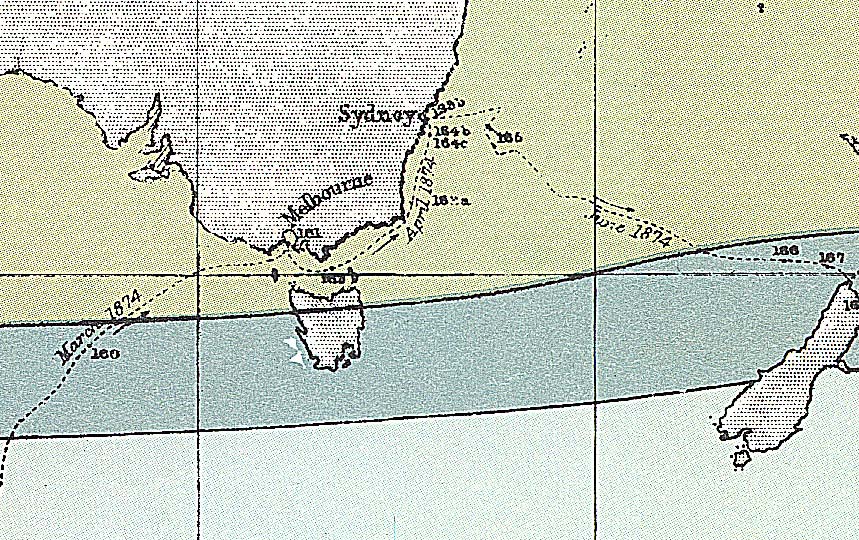

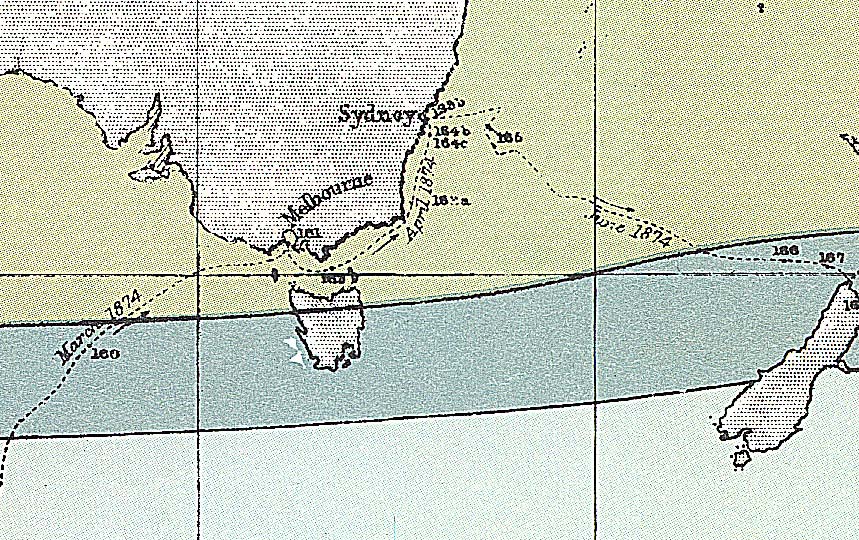

On 2 April 1874 a major scientific event occurred offshore to the north west of Flinders Island when the research vessel H.M.S. Challenger hove to and took its 162nd sounding of the ocean floor since leaving England in December 1872.

The Challenger voyage was an extraordinary undertaking to sample the oceans of the world.

Its report was hailed at the time as "the greatest advance in the knowledge of our planet since the celebrated discoveries of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries."

This Bass Strait sounding was one of only a handful taken in Australia as the vessel sailed up from the southern oceans to Melbourne and thence to Sydney en route to New Zealand.

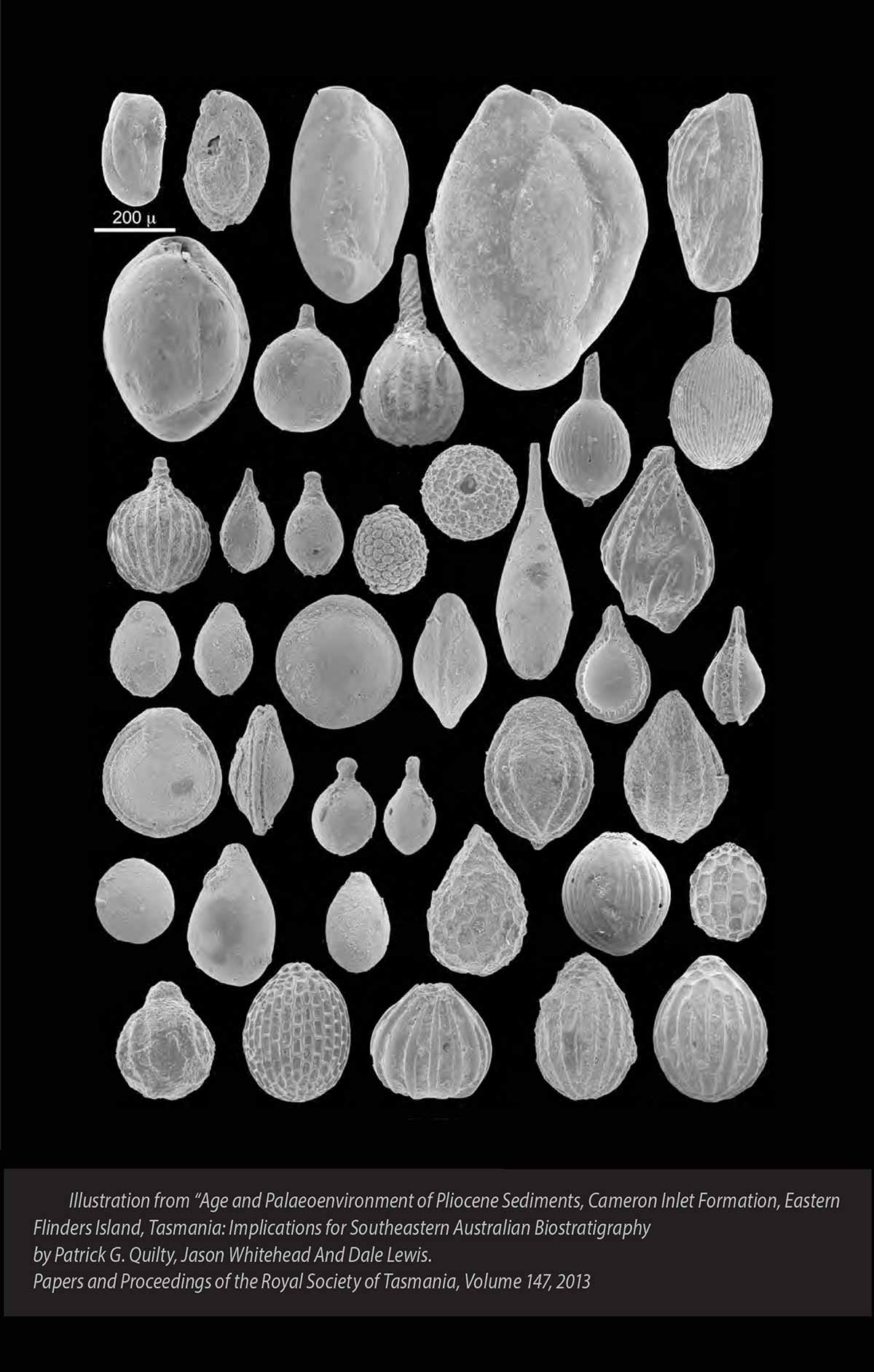

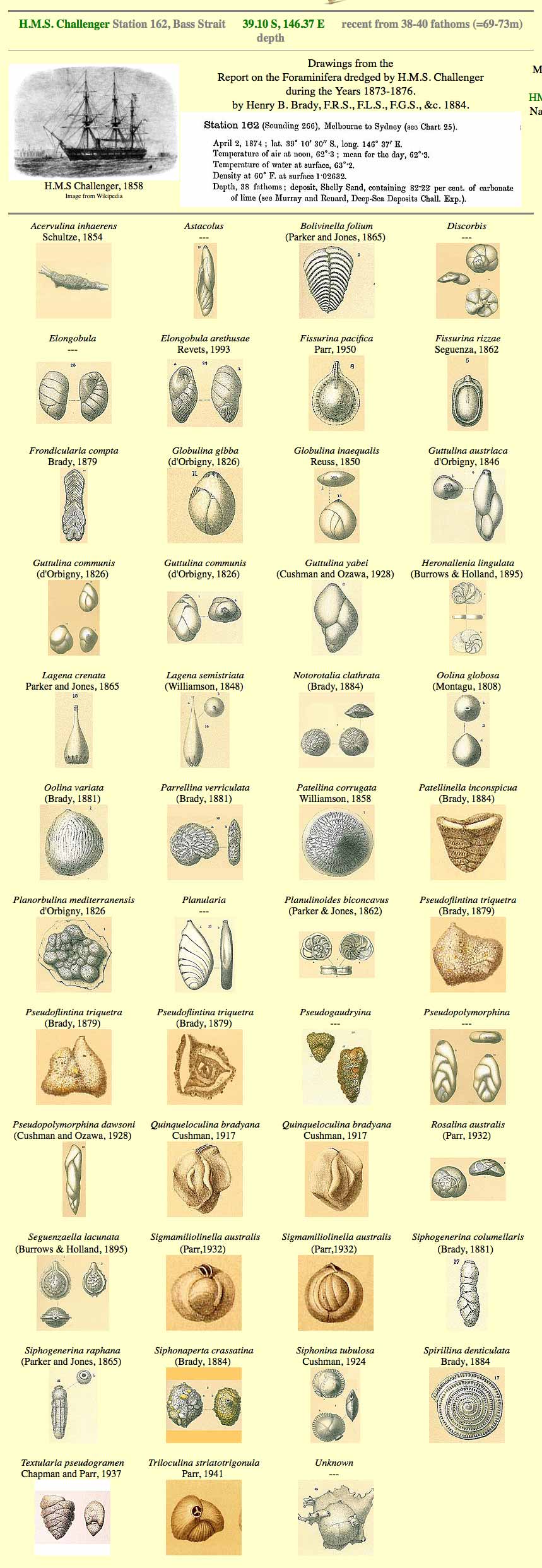

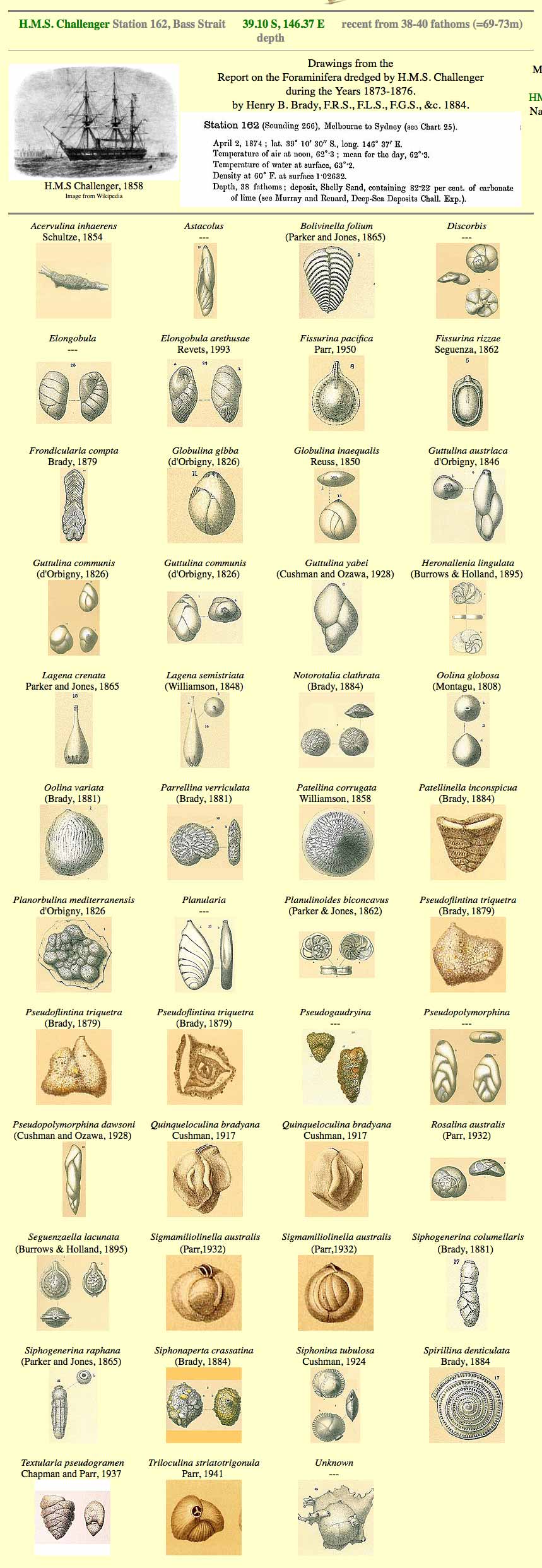

The remarkable array of tiny foraminifera shells it dredged up from Bass Strait that day has been recorded at www.foraminifera.eu

These are of special relevance to the geological story here at the southern end of Flinders Island as it was forams such as these that comprise the calcareous sands we see around us in the limestones on the island today.

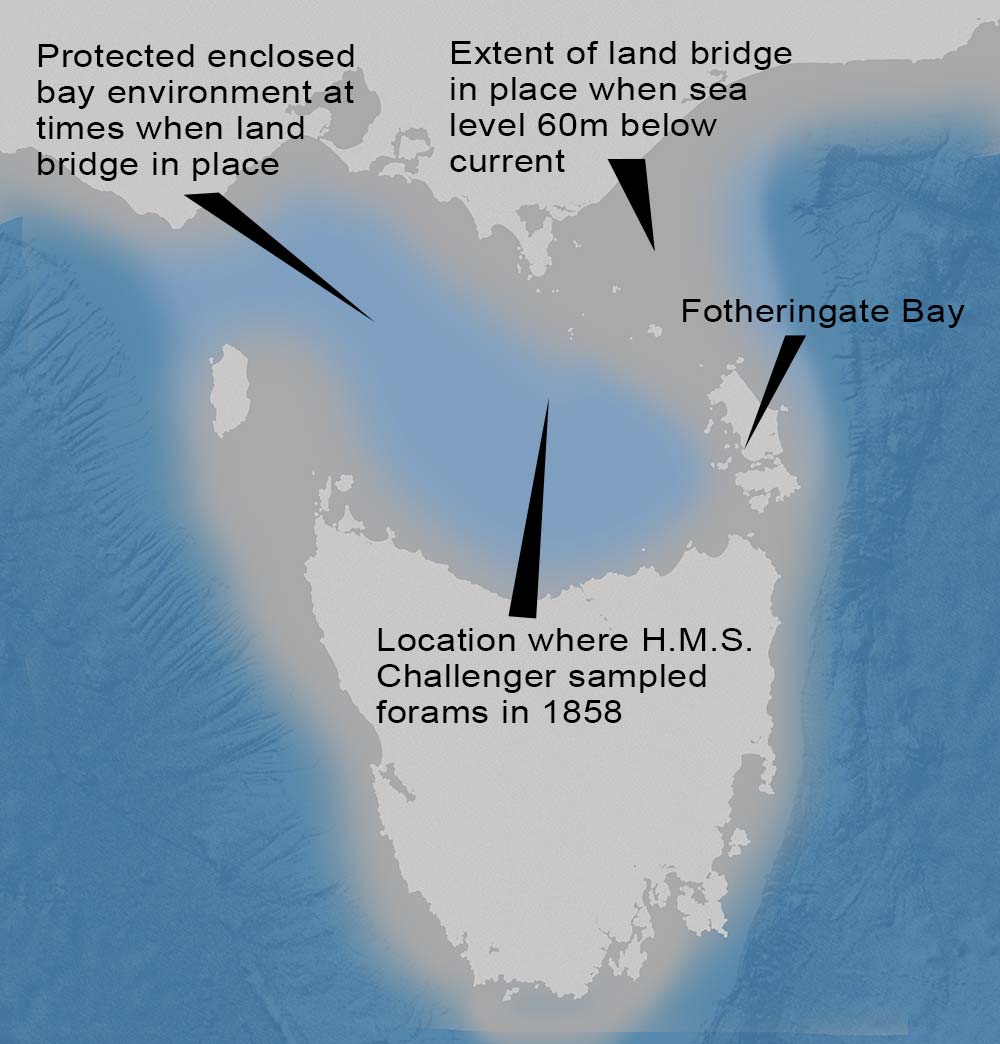

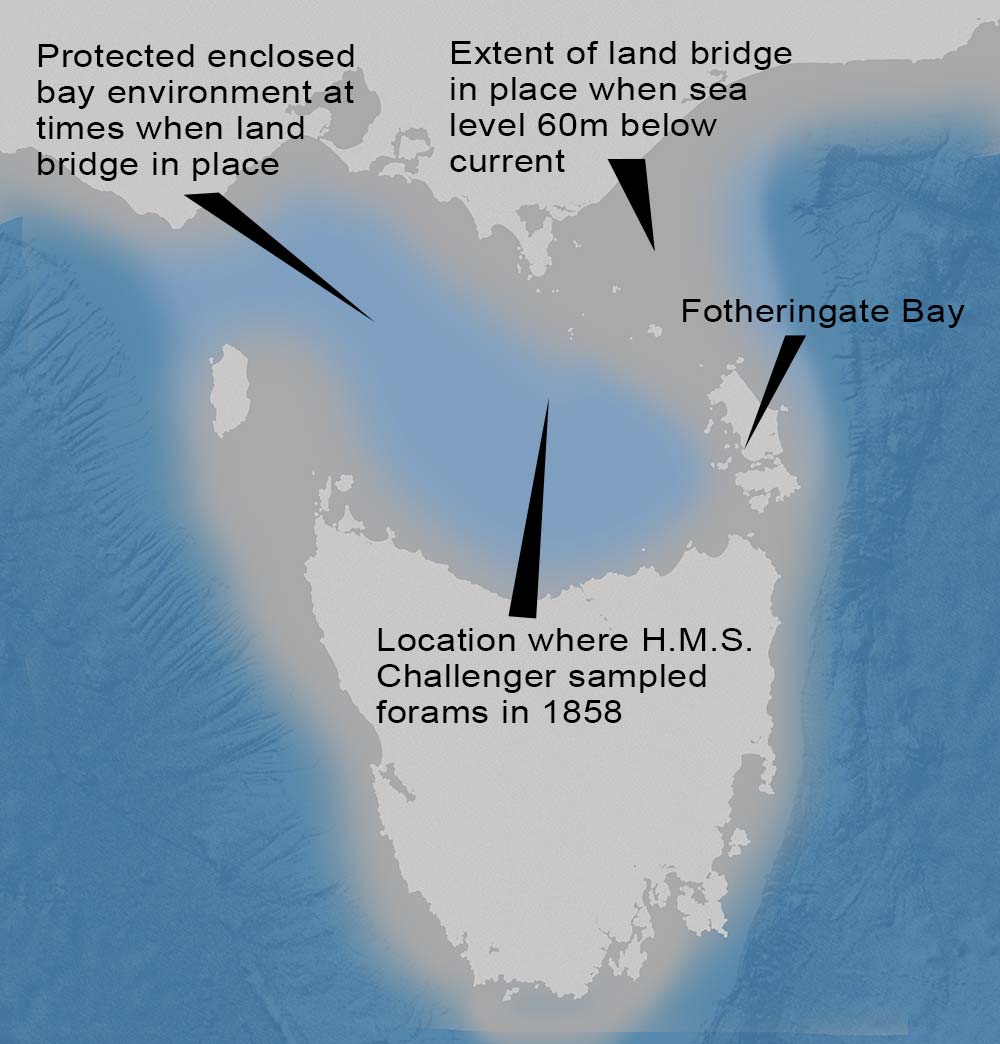

Over the past 2.5 million years countless generations of forams would have been left high and dry as the sea level cycles rose and subsided in the shallow bay waters that existed west of here for much of the last ice age.

As the water receded leaving the exposed sea bed in its wake, these foram shells would have been blown westwards by the prevailing roaring 40s winds.

When they were stopped in their western journey at the base of the high escarpments on Flinders Island, the shells then built up into the layers of calcareous sand that draped over the basement granite rocks in this local area.

Thanks to the work of the Challenger back in the 1872, we today have a special insight into this fascinating geological process at work on the landscapes of the Furneaux Group.